I’m going to share some information from an old book which is a rich source on Mexican and Central American shamans and their cosmologies: Daniel G. Brinton, Nagualism. A Study Of Native American Folk-Lore And History. Philadelphia: Maccalla & Company, 1894. The language, while Victorian and somewhat romanticized in places, is less racist and sexist than many writers of that time (in spite of the standard male-default language). And he is critical of the colonial repression of Indigenous religions. Better yet, he cites original sources! My comments are in italics, everything else is quotes from Brinton and his primary sources. I’ve bolded some sections for emphasis.

First, on shapeshifting and spirit guardians, an account with similarities to the Lakota custom of going to a sacred place and crying for a vision:

The earliest description I find of its particular rites is that which the historian Herrera gives, as they prevailed in 1530, in the province of Cerquin, in the mountainous parts of Honduras. It is as follows :

“The Devil was accustomed to deceive these natives by appearing to them in the form of a lion, tiger, coyote, lizard, snake, bird, or other animal. To these appearances they apply the name Naguals, which is as much as to say, guardians or companions ; and when such an animal dies, so does the Indian to whom it was assigned. The way such an alliance was formed was thus : The Indian repaired to some very retired spot and there appealed to the streams, rocks and trees around him, and weeping, implored for himself the favors they had conferred on his ancestors. He then sacrificed a dog or a fowl, and drew blood from his tongue, or his ears, or other parts of his body, and turned to sleep. Either in his dreams or half awake, he would see some one of those animals or birds above mentioned, who would say to him, ‘On such a day go hunting and the first animal or bird you see will be my form, and I shall remain your companion and Nagual for all time.’ Thus their friendship became so close that when one died so did the other ; and without such a Nagual the natives believe no one can become rich or powerful.” [4-5]

This region of Cerquin, which the author describes as Maya country in the mountains east of Copan (one of the ancient temple cities) has a tradition which rises above the usual masculinizing language.

Such, in Honduras, was Coamizagual, queen of Cerquin, versed in all occult science, who died not, but at the close of her earthly career rose to heaven in the form of a beautiful bird, amid the roll of thunder and the flash of lightning. [34. A footnote says, ‘The story is given in Herrera, Hist, de las Indias, Dec. iv, Lib. viii, cap. 4. The name Coamizagual is translated in the account as ” Flying Tigress.” I cannot assign it this sense in any dialect.’]

What a great name! This bears further investigation. A few page later, more details are provided about Coamizagual. Here she is unnamed here but recognizable from the first account:

“They say further that [Votan] once dwelt in Huehuetan, a town in the province of Soconusco. Near there, at the place called Tlazoaloyan, he constructed, hy blowing with his breath, a dark house, and put tapirs in the river, and in the house a great treasure, and left all in charge of a noble lady, assisted by guardians (tlapiane) to preserve. This treasure

consisted of earthenware vases with covers of the same material; a stone, on which were inscribed the fluures of the ancient native heroes as found in the calendar; chalchiuites, which are green stones ; and other superstitious objects. “All of these were taken from the cave, and publicly burned in the plaza of Huehuetan on the occasion of our first diocesan visit there in 1691, having been delivered to us by the lady in charge and the guardians. All the Indians have great respect for this Votan, and in some places they call him ‘the Heart of the Towns.’ “* [39, from Constituciones Diocesanas, pp. 10]

The above account gives a glimpse of the systematic destruction of the Maya’s sacred treasures, corresponding to the confiscation and burning of their codices, an incalculable loss.

A remarkable feature in this mysterious society was the exalted position it assigned to Women. Not only were they admitted to the most esoteric degrees, but in repeated instances they occupied the very highest posts in the organization. According to the traditions of the Tzentals and Pipils of Chiapas, when their national hero, Votan, constructed by the breath of his mouth his darkened shrine at Tlazoaloyan, in Soconusco, he deposited in it the sacred books and holy relics, and constituted a college of venerable sages to be its guardians; but placed them all in subjection to a high priestess, whose powers were absolute. [33, citing Nunez de la Vega, Constituciones Diocesanas, p. 10, and Brasseur de Bourbourg, Histoire des Nat. Civ. de Mexique, Tom. i, p. 74.]

The veracious Pascual de Andagoya asserts from his own knowledge that some of these female adepts had attained the rare and peculiar power of being in two places at once, as much as a league and a half apart … [33, quoted from Herrera, Historia de las Indias Occidentales, Dec. ii, Lib. iii, cap. 5] and the repeated references to them in the Spanish writings of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries confirm the dread in which they were held and the extensive influence they were known to control. In the sacraments of Nagualism, Woman was the primate and hierophant.

Judging from the archaeological record, that is an overstatement, although women were certainly active as shamans and curanderas. Female oracles were important among the Maya as late as the 19th century.

This was a lineal inheritance from pre-Columbian times. In many native American legends, as in others from the old world, some powerful enchantress is remembered as the founder of the State, mistress of men through the potency of her magic powers. [33]

Such, among the Aztecs, was the sorceress who built the city of Mallinalco, on the road from Mexico to Michoacan, famous even after the conquest for the skill of its magicians, who claimed descent from her. [34, citing Acosta, Hist. Nat. y Moral de las Indias, Lib. vii, cap. 5]

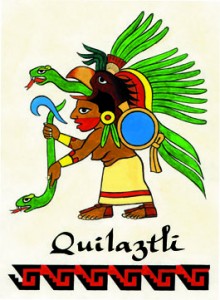

According to an author intimately familiar with the Mexican nagualists, the art they claimed to possess of transforming themselves into the lower animals was taught their predecessors by a woman, a native Circe, a mighty enchantress, whose usual name was Quilaztli (the etymology of which is unknown), but who bore also four others, representing her four metamorphoses, Cohuacihuatl [Cihuacoatl] the Serpent Woman; Quauhcihuatl, the Eagle Woman; Yaocihuatl, the Warrior Woman; and Tzitzimecihuatl, the Specter Woman. [34]

This piece is most interesting because he provides the Aztec name which Zelia Nuttal translated as Underworld Woman, here rendered as Spectre Woman. More on Quilaztli. A footnote gives further sources and details:

Jacinto de la Serna, Manual de Ministros, p. 138. Sahagun identifies Quilaztli with Tonantzin, the common mother of mankind and goddess of child-birth (Historia de Nueva España, Lib. i, cap. 6, Lib. vi, cap. 27). Further particulars of her are related by Torquemada, Monarquía Indiana, Lib. 11, cap- 2. The tzitzime were mysterious elemental powers, who, the Nahuas believed, were destined finally to destroy the present world (Sahagun, I c., Lib. vi, cap. 8). The word means “flying haired” (Serna).

The Tzitzimime were much more that this, as a quick-and-dirty check on Wikipedia shows:

In Aztec mythology, a tzitzimitl (plural tzitzimimeh) is a deity associated with stars. They were depicted as skeletal female figures wearing skirts often with skull and crossbone designs. In Postconquest descriptions they are often described as “demons” or “devils” – but this does not necessarily reflect their function in the prehispanic belief system of the Aztecs.

The Tzitzimimeh were female deities … associated with the Cihuateteo and other female deities such as Tlaltecuhtli, Coatlicue, Citlalinicue and Cihuacoatl and they were worshipped by midwives and parturient women. The leader of the tzitzimime was the Goddess Itzpapalotl who was the ruler of Tamoanchan – the paradise where the Tzitzimimeh resided.

The Tzitzimimeh were also associated with the stars and especially the stars that can be seen around the sun during a solar eclipse. This was interpreted as the Tzitzimimeh attacking the sun, this caused the belief that during a solar eclipse, the tzitzimime would descend to the earth and devour human beings. The Tzitzimimeh were also feared during other ominous periods of the Aztec world, such as during the five unlucky days called Nemontemi which marked an unstable period of the aztec year count, and during the New Fire ceremony marking the beginning of a new calendar round – both were periods associated with the fear of change.

The Tzitzimimeh had a double role in Aztec religion: they were protectresses of the feminine and progenitresses of mankind. But they were also powerful and dangerous, especially in periods of cosmic instability. [From: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tzitzimitl ]

Returning to Brinton:

We read in the chronicles of ancient Mexico that when Nezahualpilli, the king, oppressed the tribes of the coast, the tierra caliente, they sent against him, not their warriors, but their witches. These cast upon him their fatal spells, so that when he walked forth from his palace, blood burst from his mouth, and he fell prone and dead. [34, from Torquemada, Monarquia Indiana, Lib. ii, cap. 62]

Hard to tell if this is authentic Indian tradition or Spanish interpolation. But check this:

What the old historian, Father Joseph de Acosta, tells us about the clairvoyants and telepaths of the aborigines might well stand for a description of their modern representatives:

“Some of these sorcerers take any shape they choose, and fly through the air with wonderful rapidity and for long distances. They will tell what is taking place in remote localities long before the news could possibly arrive. The Spaniards have known them to report mutinies, battles, revolts and deaths, occurring two hundred or three hundred leagues distant, on the very day they took place, or the day after. To practice this art the sorcerers, usually old women, shut themselves in a house, and intoxicate themselves to the degree of losing their reason. The next day they are ready to reply to questions.” [9-10]

–Acosta, De la Historia Moral de Indias, Lib. cap. 26

Emphasis added! Unfortunately, Brinton does not say whether this is Mexico or some other country.

Max Dashu

The full text of Nagualism can be downloaded here: http://hdl.handle.net/2186/ksl:brinag00/brinag00.pdf

To be continued…