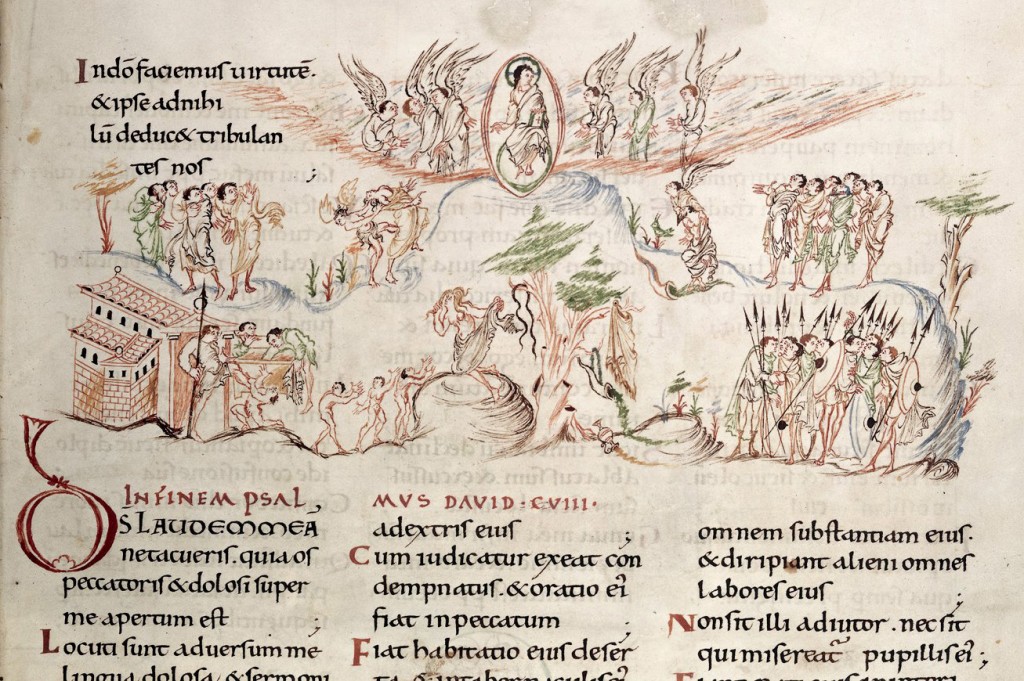

Another mystery solved. Thanks to the British Library’s online database of Old English manuscripts, i’ve finally discovered what biblical passage was illustrated by one of the most intriguing Pagan-themed medieval drawings. It appears in the Harley Psalter, thought to have been created at Canterbury circa 1020-40, as a copy of the 9th century Utrecht Psalter. Here’s the picture (click to enlarge):

I wasn’t sure what biblical passage this illustrated, though i could see the word Psalmus, and now can make out the Roman numerals for 108. But the picture clearly reflected medieval Christian themes from Europe, and what has intrigued me since the early 1980s is its evocation of the clergy’s campaign against folk goddesses. This repression of female deities in popular religion is attested by numerous episcopal decrees and priestly confessional manuals, including the Corrector Burchardi, the Canon Episcopi, and earlier writings by Regino of Prum and Raterius of Verona.

What’s going on in this picture? In the lower panel, naked Pagans pray to a Goddess who is dancing on a stone. Beside her is a Tree of Life, which has a snake, garland, streaming libation vessel, and cornucopia. It could be argued that the Snake and Tree are inspired by Genesis, except that they are also common themes in Germanic religion, for example in the Matronae stones of the Rhineland (2nd-3rd century CE), and indeed around the world. So they predate the christianization of western Europe. The cornucopia originates with the Roman goddesses, particularly Terra Ops, Ceres, and Fortuna, whose bounty it symbolizes. (It spread far and wide during the empire, not only to Britain, Gaul and Germany, but also to Egypt, added to the attributes of Isis, and into southwest Asia, also in association with goddesses.) Garlands were also widely used in animist ceremonies throughout Europe. As late as 1431, Jeanne d’Arc was accused of hanging garlands on the Fairy Tree for le beau Mai, the old pagan holyday of May Day. The inquisitors and theologians still saw this as a damnable Pagan act.

The goddess is bare-breasted, but her cape or mantle hangs from the tree. Some medieval images of witches (for example, a stone panel at Lyons cathedral, and a German church mural in Schleswig, near Denmark) show witches as naked women clad only in capes. They are riding on animals, or on a broomstick. It is this very theme of shamanic theme of women’s flight on the backs of animals that the clergy targeted for repression. They reinterpreted the Women Who Go by Night with the Goddess, in diabolist terms. The Goddess was “really” the devil. Advanced early on by church fathers, this doctrine persisted in Frankish texts about the worship of “Diana” (the interpretatio romana often obscured the names of local ethnic goddesses) or of “the witch Holda” (the German goddess Holle).

Caped witch riding goat (and whirling a hare), relief from door of Lyons Cathedral. Directly opposite, another panel shows a lord in a castle tower ordering armed men with mastiffs to go after the witch.

The central theme in this Harley Psalter picture is supercession. The christian god-the-son is depicted above the goddess, as if replacing her. Not only is he placed above her spatially, but like her, he rests on a stone, and he too has the cornucopia streaming blessings. These are not Christian themes! but they were too deeply entrenched in the culture to be done away with. So they were appropriated as a step in the process of supplanting Goddess reverence. Between the rival deities, a barebreasted woman tries to approach Jesus, but an angel drags her away by her hair. I think this is significant since she is one of very few females in the Harley Psalter illustrations. You’ll note that all the other figures in the picture, even the Pagan worshippers and the angels, are male.

At lower left, soldiers are looting from a chest and kicking a man who is begging for mercy. Two of the Goddess worshippers are looking nervously over their shoulders at the soldiers, worried that they will be next. To me, this picture represents state attacks on pagans. Confiscation of their goods was one of the primary punishments, along with flogging and enslavement, for those who adhered to older ethnic religions in the early middle ages. (It was primarily secular rulers who carried out these penalties, although priestly influence is clear, and bishops had powers both as secular and ecclesiastical lords.) The image comes from the portion of the Harley Psalter which was directly copied from the Utrecht Psalter. That would date the scene to the 9th century, when such punishments were still widely inflicted on Pagans.

The picture appears as an illustration to Psalm 108. At first, reading the psalm, with its standard exaltation of the Hebrew god, you might wonder: What does this picture have to do with that? The answer appears toward the end of the psalm, where the biblical god claims various territories in the land of Israel. Singled out for humiliation are Pagan lands in modern Jordan, traditional enemies of the Hebrews: “Moab is my washbasin, on Edom I toss my sandal… Who will bring me to the fortified city? Who will lead me to Edom?” In the mind of the monks who illuminated this manuscript, the common thread seems to be the conquest and suppression of Pagans.

The biblical psalm doesn’t say a word about goddesses, but the Harley Psalter (or its Carolingian model, the Utrecht) understands this supercession as being specifically the displacement of Goddess veneration by the Christian god. In another picture, he is exalted over Mother Earth who is shown submissively gazing up at him, surrounded by her sons (no daughters). She still has the cornucopia, from which watery essence is flowing toward a tree — and the bare-breasted Mother is wearing a cape or mantle.

Eorthan Modor was just impossible for them to get rid of. She pops up even in the margins of Christian scriptures, on the ivory covers of prayer books, in murals of monasteries. In fact, she will outlive all human constructs — and that goes double for the concoctions of patriarchal theologians.

Edit May 2016:

The more I consider the symbolism of this goddess in the Harley Psalter (and the Utrecht Psalter on which it was modeled), the more likely it seems to me that she was intended to represent Herodias. The painting is contemporary with the earliest references to the Witches’ Goddess, in the Libri Duo of Regino of Prum and the Praeloquia of Raterius of Verona. The dancing woman ties in with the developing priestly myth of Herodias based on biblical accounts of the dance of Salome (the daughter of Herodias). This story came into wider circulation through the Heliand, a vernacular retelling of the Christian Bible in Germanic epic style that was commissioned by Frankish emperor Louis the Pious in an effort to convert the Old Saxons.

The renaming of a Germanic folk goddess as Herodias, the sexualized villain of the Christian Bible, is discussed in my book Witches and Pagans: Women in European Folk Religion, 2016. The story has little to do with the historical reality of Herodias or her daughter Salome (who was also named Herodias), except that in her own time she was demonized for defying the sexual double standard.

Coming from a dynastic family did not mean that Herodias had an easy life. She was orphaned by her grandfather Herod “the great” [hate those titles] who executed her father and his brother in 7 bce. Then he arranged her marriage to Herod II, a move dictated by dynastic politics. Herodias suffered in this marriage, so she made the bold move (unthinkable in her social context) of divorcing her husband. This act of self defense earned her public denunications from John the Baptist and then from the historian Josephus.

Josephus wrote, “Herodias took it upon her to confound the laws of our country, and divorced her husband while he was alive, and was [then] married to Herod Antipas.” [Antiquities of the Jews, www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/2848] The Gospels of Matthew and Luke say that her remarriage caused John the Baptist to publicly denounce her. Herodias’ second husband Herod Antipas had John arrested and executed. The Christian Bible recounts a fable that Herodias got her daughter Salome to dance for the king and demand John’s head in return. Modern scholars doubt that, and in fact Josephus says Herod Antipas executed him, fearing that he was stoking sedition.

But the gospel writers make her the villain, drawing on current Roman stories in which a prostitute makes the killing of a man her price. These unfair characterizations have lasted the better part of two millennia, as witness countless orientalizing paintings of the story.

Herodias by Paul Delaroche

Copyright 2012 Max Dashu