One of the earliest descriptions of South American holy women was written by Martin Dobrizhoffer, a Jesuit missionary in Paraguay in the mid-1700s. He lived first among the Guaraní and then the “Abipones.” This was a Spanish name, not their own, for a people who no longer exist, also called the Callaga or Kalyaga). They lived in what is now called the lower Bermejo river in Paraguay, in the southern part of the Chaco region (now transected by the borders of Brazil and Argentina). They spoke a Guaicurú language related to those of the neighboringToba and Mocoví peoples.

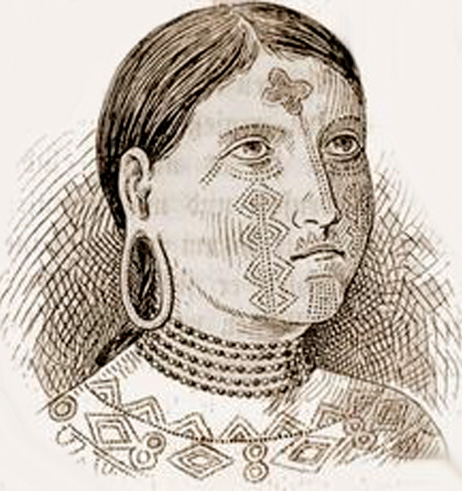

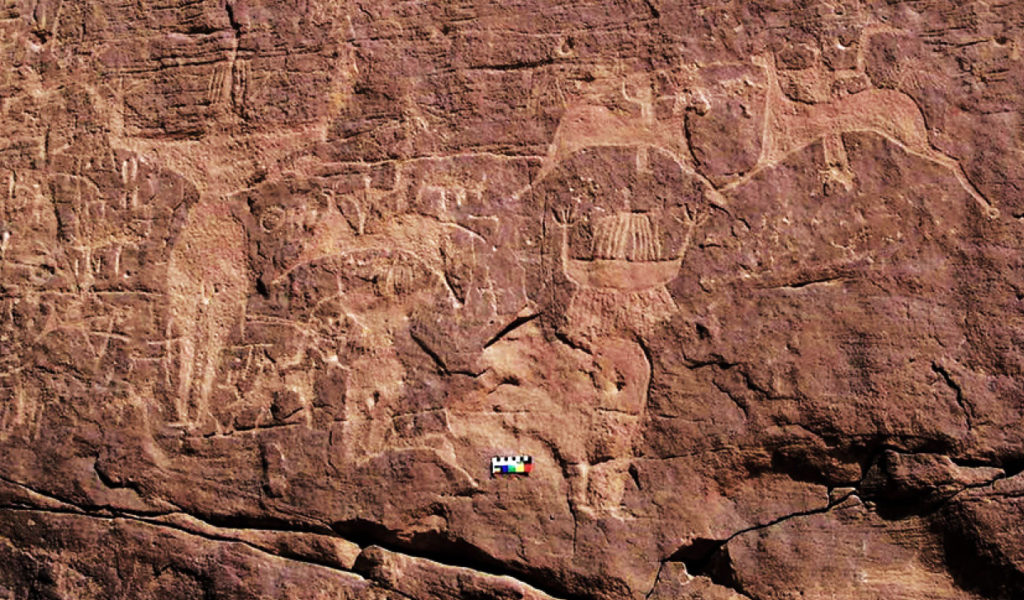

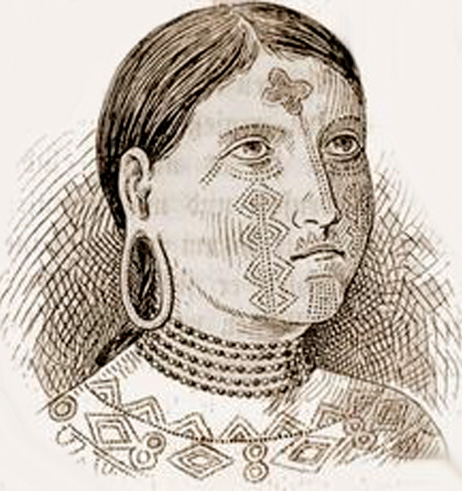

Abipon woman, with tattoos, common in the Chaco into the 20th century

The Abipones originally lived mainly by hunting and gathering, with some farming. By 1641 they had the horse, and took to raiding cattle and horses from European settlers, including in the nascent cities of Asunción. They were driven south by the Spanish and Toba, into what is now northern Argentina, and European settlers took their lands. From 1710 the Spanish sent military forces against the Abipones, forcing them to settle in colonias, and by 1750 the Jesuits had set up missions. Dobrizhoffer was among these missionaries. During the time he was there, more than half of the Abipones had died of diseases from Europe, as well as from wars with the colonials and also with their linguistic relatives, the Toba and Mocobí.

Martin Dobrizhoffer, An Account of the Abipones, an equestrian people of Paraguay. Vol II. London: John Murray, 1822 (The book was written before 1784, and translated and published by Sara Coleridge, to pay for her brother’s college expenses.)

Martin Dobrizhoffer, An Account of the Abipones, an equestrian people of Paraguay. Written around 1780.

The Jesuit missionary’s account is deeply stained—as they all are—with a belief in European and Christian supremacy. He insults the Abipones as “fools, idiots, and madmen” and disparages their religion as devilish. [64] So why read the book at all? It is the primary historical source on this society, and it does contain valuable information in spite of the author’s manifest bias, especially about the female keebèt who were important ceremonial leaders and healers. But it is necessary to read through and under Dobrizhoffer’s beliefs in order to glimpse how the women’s chant, dances, and healings might have looked, and to visual their sacrality, the thing that he is most eager to deny.

Dobrizhoffer occasionally admits that the Abipones had many good qualities. He praises their “modest cheerfulness… gentleness and kindness.” He relates that they are humorous and good-natured: “they never break out into clamours, threats, and reproaches…” We learn further that they are unfailingly polite in their assemblies, never interrupting. [136]

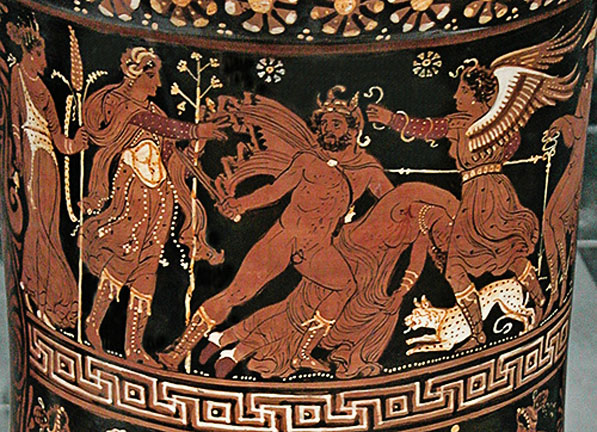

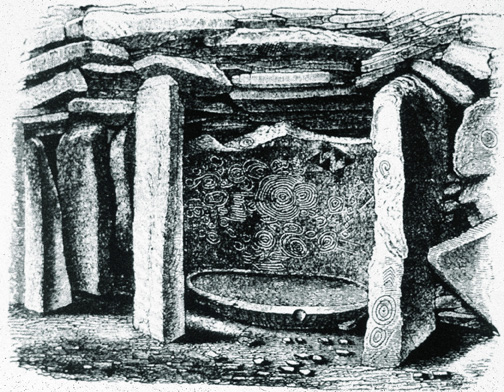

Abipones

The author provides valuable descriptions of the leading role of female shamans, amidst his constant denunciations of them, often in bitterly contemptuous tones that are both misogynist and racist. He is puzzled that so much authority was vested in women, and repeatedly compares them, especially the female elders, to the Delphic oracle, the only women he had ever heard of who exercised spiritual power. His very skewed lens reports that the old women “are obstinate adherers to their ancient superstitions, and priestesses of the savage rites, strongly oppose the Christian religion…” [153]

As is common in colonial accounts of this period, shamans are described as “jugglers,” a word that originates from the French jongleurs, literally “jesters,” who were wandering minstrels, acrobats, and jugglers. This word choice implies deception and trickery, a claim that was often made by colonial observers of medicine ceremonies. Once again, there is much to criticize in this book, but the many instances of its bias are historical evidence of the colossal prejudice against indigenous spiritual philosophies as well as the spiritual leadership of women.

The Abipones called their spiritual leaders keebèt. “These rogues, who are of both sexes, profess to know and have the ability to do all things.” All the Abipones believed that they had the power “to cure all disorders, to make known distant and future events; to cause rain, hail, and tempests; to call up the shades of the dead, and consult them concerning hidden matters; to put on the form of a tiger [puma]; to handle every kind of serpent without danger…” [67]

Elsewhere the missionary refers to the high repute and broad authority of the keebèt among their people: “the jugglers perform the offices not only of soothsayers and physicians, but also of priests of the ceremonies of superstition.” [82] People also rely on the keebèt in their journeys and hunts. [76] Dobrizhoffer writes that women shamans were numerous and may even be implying that they outnumbered the men: “Female jugglers abound to such a degree, that they almost outnumber the gnats of Egypt.” [87] The pejorative tone is pervasive throughout the text, which illustrates European attitudes.

For their vision quest, prospective keebèt “are said to sit upon an aged willow, overhanging some lake, and to abstain from food for several days, till they begin to see into futurity.” Dobrizhoffer then proceeds to denounce the keebèt as deceitful people who cheat “ignorant and credulous savages” [67-68] It doesn’t occur to him that people may have seen him and other priests in that light, then and now.

The Jesuit says that all over Paraguay and Brazil, shamans “cure every kind of disease” by extracting pernicious energies from the sick person’s body and blowing in vitality: “They apply their lips to the part affected, and suck it, spitting after every suction. At intervals they draw up their breath from the very bottom of their breast, and blow upon that part of the body which is in pain. That blowing and sucking are alternately repeated.” If the person has a high fever, “four or five of these harpies fly to suck and blow it, one fastening his lips on the arm, another on the side, a third and fourth on the feet.” [249]

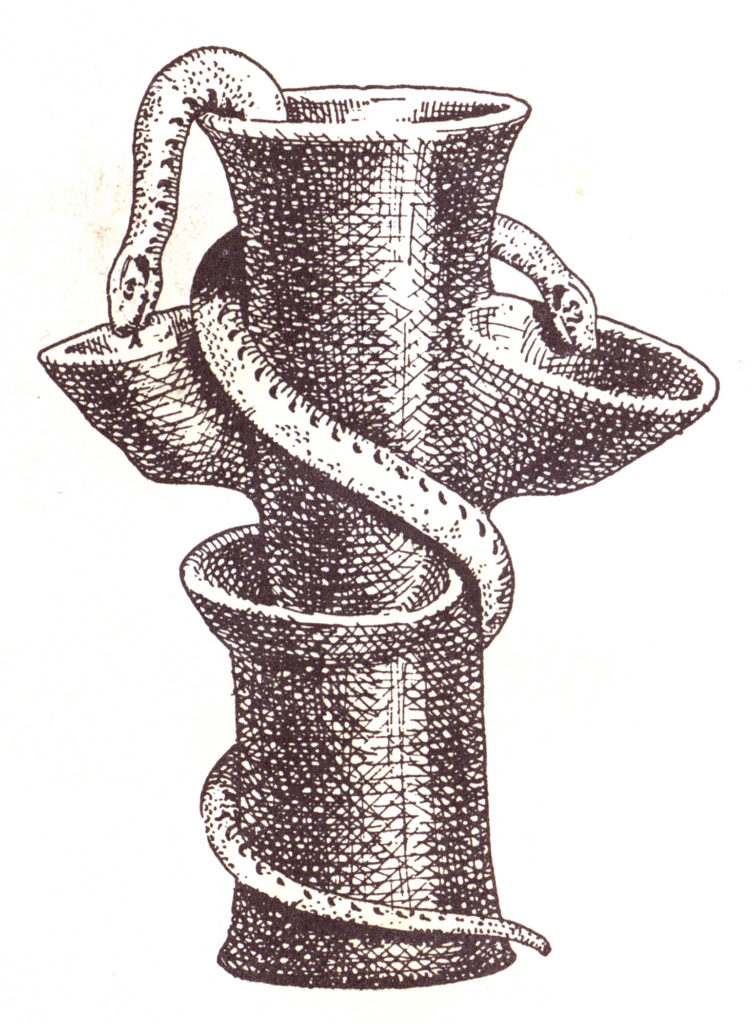

“The Guarycurùs call their physicians Nigienigis. A gourd filled with hard seeds, and a fan of dusky emu fathers are their chief insignia, and medical instruments, which they always carry in their hands that they may be known.” [262] These answer to the feather prayer fans that are used to sweep away ailment and infuse vital power in some other cultures of the Americas.

However, there is ambiguity in the shamans’ status. Some societies are known to have suspected medicine people of sorcery, or to blame them if cures do not work: “If any one dies of a disease, the relations persecute the physicians most terribly, as the author of his death. If a Cacique [chief] dies, they put all the physicians to death, that they might not fly elsewhere.” [262] This must be an exaggeration, or they’d have no more healers.

Whatever ambivalence they may have had, the Abipones had great reverence for their dead keebèt, like the San, Mongols, and so many other peoples on other continents. “In their migrations, they reverently carry with them their bones and other relics as sacred pledges. Whenever the Abipones see a fiery meteor, or hear it thunder three or four times, these simpletons believe that one of their jugglers [sic] is dead, and that this thunder and lightning are his funeral obsequies.” [75-76]

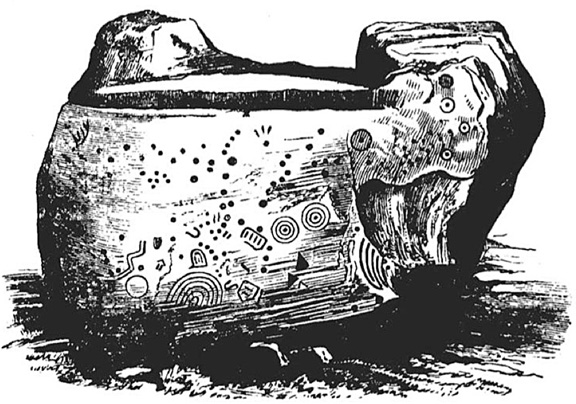

“Abipon Faces,” possibly taken from Dobrizhoffer’s book. Women on the left. Both sexes shaved their hair in the middle of the head.

Women as Ceremonial Leaders

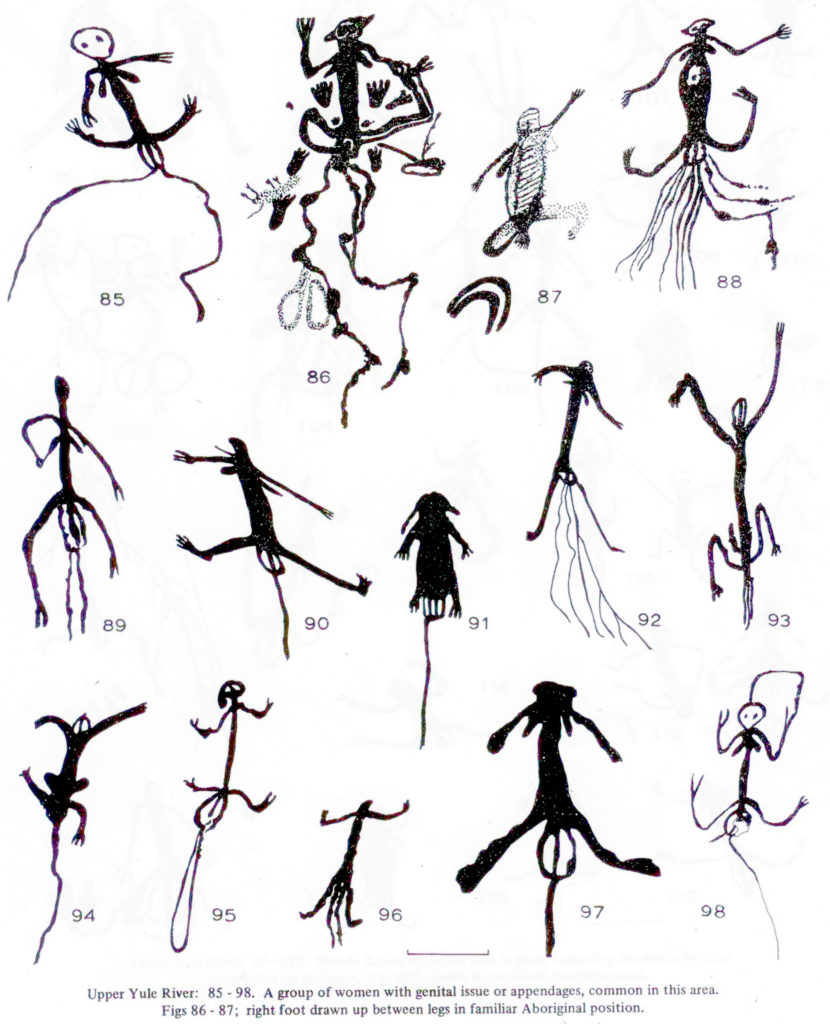

Celebrations were held to honor “our grandfather Pleiades” with mead and an all night festival, with torches blazing, women singing loudly, people laughing and applauding. “Some female juggler, who conducts the festive ceremonies, dances at intervals, rattling a gourd full of hardish fruitseeds to musical time, and, whirling round to the right with one foot, and to the left with another, without every removing from one spot, or in the least varying her motions.” Trumpets sounded and the assembled people made a loud noise by striking their lips with their hands.

Strict decorum was observed, with women and men sitting separately. “The female dancer, the priestess of these ridiculous [sic] ceremonies… rubs the thighs of some of the men with her gourds, and in the name of their grandfather, promises them swiftness in pursuing enemies and wild beasts. At the same time the new male and female jugglers… are initiated with many ceremonies.” [65-66]

[[[ The Pleiades constellation was revered across the world. Its appearance above the horizon after a season out of human view often signaled the beginning of agricultural or other seasonal cycles. The ceremony Dobrizhoffer describes here may well have been New Year for the Abipones, a time when future undertakings were blessed. They called the constellation “grandfather,” but a great many cultures from North Dakota to Australia connected its stars with a group of sisters. They figured in traditions of the Lakota about the geologic formation known to the Lakota as Mato Tipila, Bear Lodge, and the Cheyenne, and Arapaho have similar names for it. The sisters were chased by a bear, and took refuge on a great rock. Great Spirit raised the stone to save them from the bear; the long slits in the rock were made by the bear’s claws as it tried to climb and reach the women, who became the Pleiades. Settlers call the rock in northeastern Wyoming “Devil’s Tower,” which you may remember from the film E.T.) ]]]

The Abipones were probably patrilineal, though matrilineal societies still exist in the Chaco region. They became a warrior society who displaced other groups after being driven themselves from their original lands. The children of chiefs were seen as noble, but this ranking was not necessarily passed on to the unworthy. If the children were considered stupid, cowardly or foolish, “they make them of no account” and “choose for rulers and leaders others of the common people, whom they know to be active, sagacious, brave, and modest.” [440]

Still, they celebrated and rejoiced when a cacique’s son was born: “the whole crowd of girls, bearing palm boughs in their hands” would go to the baby’s house “amid festive acclamations; they run round the roof and side of it, shaking the palm boughs” to ensure he will be a great warrior. You may think chief, son, warrior: old story, patriarchal system; but the interesting thing to me is the female leadership (and athleticism) in these celebrations:

The strongest of the women is covered from the loins to the legs, with a sort of apron made of the longer ostrich feathers.” This woman goes around to all the houses in the midst of a female band, carrying a twisted hide club with which she “whips, puts to flight, and pursues all the men that she finds in every house, and those that are met by the way are soundly beaten by the girls, with the palm boughs. The first day is passed in this running up and down, amidst the laughter of the flagellated men.

The second day, bands of girls wrestle with each other, and the boys do the same separately in another place. On the third day, the people dance, males on one side, females on the other. “They all join hands til a circle is formed, an old woman, the directress of the dance going round striking a gourd: and when after a whirling for some time, they grow giddy, they rest at intervals, and then renew their dancing… [216-17]

On the fourth day, the woman with the apron of ostrich feathers traverses the town, surrounded by girls, challenging the stoutest and strongest woman she finds in every house, to contend with her in the street; and now throwing her adversary, now being herself thrown, affords an amusing spectacle to the assembled people. [217-18]

The rest of the eight-day festival continued with sports, men’s drinking parties, songs and drumming. [217-18] This account compares to women’s wrestling events in Brazil where, among the Xinguano, the Hukahuka wrestlers are accompanied by ceremonies, dance and singing. In the mid-20th century, Nuba women wrestled in Sudan, and in Mongolia, Marco Polo’s recounted stories about the female wrestler Khutulun.

Dobrizhoffer relates that the Abipones were in constant fear of attack by enemies, and always on the watch. They would consult spirits to get protection and warning of possible raids, and here again old female shamans presided:

About the beginning of the night a company of old women assemble in a huge tent. The mistress of the band, an old woman remarkable for wrinkles and grey hairs, strikes every now and then two large discordant drums, at intervals of four sounds… she with a harsh voice, mutters kinds of songs, like a person mourning. The surrounding women, with their hair dishevelled and their breasts bare, rattle gourds, and loudly chant funeral verses, which are accompanied by a continual motion of the feet, and tossing about of the arms. [72]

Others beat hand drums with sticks, and the ceremony continued all night long:

At day-break all flock to the old woman’s tent, as to a Delphic oracle. The singers receive little presents, and are anxiously asked what their grandfather has said. … Sometimes the devil is consulted by different women, in different tents, the same night. He describes differing opinions and disputes over what is true. Sometimes shamans are hidden under a bull-hide, chanting verses; at some point they declare that a shade has come, and inquire about future events. [72-74]

Dobrizhoffer was struck by the fact that even Spanish captives believed in these ceremonies. They had been around long enough to see the prophecies come true, it appears.

Another ceremony was held when a worthy man (but see below) was promoted to noble rank. He underwent a process of initiation, sitting for three days with a black bead placed on his tongue, without speaking, eating or drinking. [441] After this, “all the women flock to the threshold of his tent.” Pulling the clothes off their upper bodies and loosing their hair, they stand in a line and chant, dance, and shake gourds, lamenting for the man’s ancestors. The candidate dresses in his best, carries a spear while riding a caparisoned horse. He gallops north, then returns and goes to a tent “where sits an old female juggler, the priestess of the ceremonies, who is afterwards to inaugurate the candidate with solemn rites. [441-42]

The matrons strike their lips and applaud. The old woman seated on a hide gives a short speech, which the people receive with great reverence. Then the candidate rides out to each of the other directions in turn, every time returning to the old woman who “pours forth her eloquence.” After that, everyone goes to the sacred tent, where an old woman shaves the man’s head. Then she “pronounces a panegyric” on his noble qualities and exploits. They spread his new names and the women pronounce it while striking their lips with their hands. [443-44]

All this places great emphasis on the male, but Dobrizhoffer lets slip a mention that women also were honored in this same way: “It is remarkable that many of the women arrive at this degree of honour, and nobility, enjoy the privileges of the Höcheri [“high ones”? seems to be German], and use their dialect. The names of these females end in En, as those of the men in In.” This seems to imply that the Abipon language had gender-specific dialects, as various American and North Asian cultures do.

Women also led the funerary rites. When someone was dying, “the old women, who are either related to the person, or famed for medical skill, flock to his house. They stand in a row round the sick man’s bed, with disheveled hair and bare shoulders, striking a gourd, the mournful sound of which they accompany with violent motion of the feet and arms, and loud vociferations.” The most senior or greatest healer stands close to the man’s head “and strikes an immense military drum.” Another occasionally moves the bullhide that covers him and sprinkles him with cold water. [265-66]

“All the married women and widows of the town crowd to the mourning,” wailing, rattling gourds, and beating hand drums. As soon as someone dies, they immediately take the body for burial. “Women are appointed to go forward on stiff steeds, to dig the grave, and honour the funeral with lamentations.” [267] The men go off for honey for their big drinking party: “we always pitied the women, upon whom devolved all the trouble of the exequies, the care of the funeral, and the labor of making the grave and of mourning.” [275] However, this seems to be more a function of their authority than the usual European stereotype of female drudges.

The name of the dead person cannot be said again, and substitutes were created: “It is the prerogative of the old women to invent these new names,” which spread rapidly. “All the friends and relations of the deceased change the names they formerly bore.” Houses were demolished, followed by nine days of mourning. There were two kinds of mourning: a public one that unmarried women perform in the streets, and another in people’s homes, by invitation only.

At set times in morning and afternoon, “all the women in the town assemble in the market-place, with their hair scattered about their shoulders, their breast and back naked, and a skin hanging from their loins.” Dobrizhoffer compares them to “Bacchanals or infernal furies” who leap and move their arms, striking gourd rattles or beating deerskin drums: “They go up and down the whole marketplace, like supplicants, walking separately but all in one very long row.” [276] The mourners shout, trill, quiver, groan, and chant mournfully. Occasionally they stop and drop their voices from high to low, and “suddenly utter a very shrill hissing.” They extol the dead person’s good qualities, and imprecate the person blamed of the death.

Women mourners also lamented by night, starting at sundown and halting at sunrise. They assembled in a house, “one of the female jugglers presiding over the party, and regulating the chaunting and other rites.” She beat on two large drums and sang the funeral lament, joined by the others with gourd rattles. This went on all night, and for eight more nights. If a woman was being mourned, there was a ceremony of breaking her pots on the ninth night. Then their chanting became more festive, still led by the old woman drummer singing in a deep voice. [277-78]

Women carried out these same ceremonies to honor the ancestors. “Few nights pass that you do not hear women mourning. This they do upon their feet,” facing the grave, always rattling their gourds. They grew louder as day approaches, shrieking and lamenting. [279] We need to remember several things here: the context of conquest and colonization, with a very high mortality rate due to epidemics from European diseases as well as the disruption of traditional economies. All this was going on in the historical moment in which Dobrizhoffer was writing his trilogy. The other thing to keep in mind is that the ancestor reverence was part of the Abipon tradition, as he himself remarks. The ceremonies were not for mourning only, but had other spiritual significance, including that of assistance in very hard times. They are likely to have been imbued with the state of emergency in which the people found themselves, in those years before they were wiped off the face of the earth.

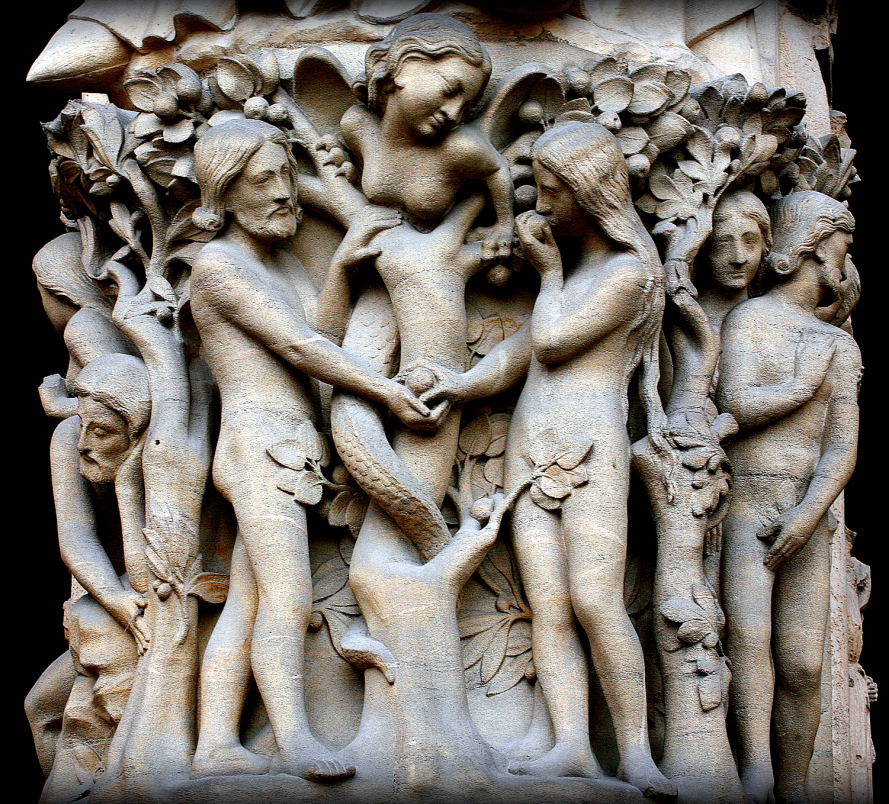

Spanish conversion attempts and Native resistance

Among the convert towns, the keebèt practiced in secret and still exerted considerable influence. The Jesuit complains that “the American jugglers… these wickedest of mortals” kept people from going to church or heeding the admonitions of priests. He writes of how Guaraní shamans sharpened the Indigenous resistance to Antonio Ruiz de Montoya: “It was not till he had repressed the authority of the remaining jugglers, and commanded the bones of eighty of the dead ones, which were universally worshipped with great honors, to be burnt in the presence of the people…” that the Spanish succeeded in overcoming them. Until the keebèt are abolished, Dobrizhoffer counsels, “nothing can be done with the savages; this I affirm on experience.” [81] This was the policy everywhere, not only in the Spanish colonies, but the English, French and Dutch ones.

One notable convert outdid himself by adopting Catholic practices like self-flagellation. He had originally acted as a scout for Spanish, but became thoroughly disilllusioned with them due to their treatment of him and other people. After the Spanish prevailed by force of arms, he did everything he could to turn people against the clergy in his role as interpreter. As much as Dobrizhoffer hated this man, he felt even more threatened by his “still more pestilent mother”:

“This woman, the chief of all the female jugglers, a hundred years old, venerable to the people on account of her wrinkles, and formidable by reason of the magic arts she was thought to be acquainted with, never ceased exhorting her countrymen to shun and detest the church…” This important female shaman was later killed by the Mocobí, “along with many others,” while fleeing the town. [145]

Women’s Status

Female chieftains are recorded for this people: “…the Abipones do not scorn to be governed by women of noble birth; for at the time that I resided in Paraguay, there was a high-born matron, to whom the Abipones gave the title of Nelareycaté, and who numbered some families in her horde.” [108] Although the Abipones were a warrior people, the missionary recounts how well they treated captives, including escaped slaves. With amazement, he reports that female captives were never raped. [147] The same reports of non-rape culture can be found in accounts from in North America, including some written by white women who had been taken captive by the Iroquois and other nations.

Things were less groovy among the Chiquitos, as we learn from the missionary’s description of their medicine people. First, let’s look at what he says about their healings. He says that the “juggler” physicians of the Chiquitos feast before doing treatments. They question patients closely about where they were, what they ate, in order to discover the cause of illness. “The juggler sucks the afflicted part once, twice, and three times. Then muttering a doleful charm, he knocks the floor on which the sick man is lying, with a club, to frighten away the soul of that animal [that has entered his body] from his patient’s body.” [262-63]

But—and here comes the sexual politics—Dobrizhoffer wrote that the male shamans blamed wives, and sometimes female shamans too, for a man’s illness. “When a husband fell ill, they used to kill the wife, thinking her the cause of his sickness…. At other times they consulted their physicians, which of the female jugglers occasioned the disease. These men, actuated either by desire of vengeance or interested motives, named whomsoever they chose, and were not required to bring any proofs of the guilt of the accused.” People came from all parts to carry out their sentence. [264]

I have to caution that the missionaries sought to cast Indian society in the worst possible light, but still it appears that inequality and scapegoating were present in whatever society this was, that the Spanish had dubbed “Chiquitos” (little ones). Dobrizhoffer does not claim that the Abipones did this. There are parallels in other parts of the world of wives being blamed and killed for causing their husbands’ deaths. But that’s another discussion. So is the expulsion of the Jesuits from Paraguay. For all their faults, including their attempt to impose their culture on the Native peoples, they did protect the Guaraní, at least, from the worst settler depredations, which included enslavement. And for that, after 150 years, the Spanish crown expelled them from the country.

What I find striking in Dobrizhoffer’s account is the importance of women as ceremonial leaders and healers. That lineage continues in the Chaco region today. There are no more Abipones, though their blood may run in the veins of other peoples. But women of other peoples, such as the Maka and Nivaclé, carry on with the circle dances, chants, and processions with ceremonial staffs topped by guanaco hoof rattles.

Maka women’s ceremony

Nivaklé women elders procession with staffs; the caption says: “The Nivaclé people in Formosa province EXIST!”

https://incupo.org.ar/el-pueblo-nivacle-en-la-provincia-de-formosa-estan/

]]>