Recently I’ve been looking at a lot of rock art, trying to uncover ancient history in Africa, Australia, and North America. One of the richest finds so far has been in southern New Mexico, which has a tremendous amount of petroglyphs and rock paintings. This has also opened up the Mogollon cultures (named after a mountain range, named after a conquistador –never a good choice for First Nations cultural histories). Most people know this culture as the Mimbres, famous for its superbly painted ceramics, but there are also the Jornada and other less famous, but no less impressive, traditions. Nearly everyone is more familiar with the northern Pueblos, which share many cultural elements and symbols.

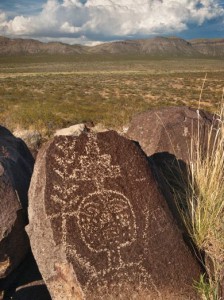

For example, this engraved rock at Three Rivers, attributed to the Jornada culture, shows a staff-like being crowned with the Tablita headdress of the Corn Maidens, and flanked by parrots like certain kachinas, such as female beings portrayed in the kiva murals at Awatovi (Pottery Mound), circa 1450 CE. (See below) The being at Three Rivers also appears to be grasping serpents in each hand.

The kiva mural at right is from Awatovi, south of the Hopi mesa villages in northern Arizona. It shows a female being with lightning emanating from the bowl she carries on her head. (The theme of thunder coming from bowls rolling in the heavens recurs from South America to China.) She is surrounded with insects indicating the presence of rain. Likewise, a modern painting of Palahiko Mana, “Water Drinking Woman” (below) shows her wearing the Tablita headdress with stepped Earth signs and corn ears. Water Drinking Woman seems to be a name for the corn itself, one of many forms of the Corn Maidens.

Going back to the Jornada culture in the south, compare the petroglyph below, from near Tularosa, New Mexico. She holds a growing plant, perhaps even corn, in her hand. (I say she because all of the images with the Tablita headdress, both in Arizona and New Mexico, are female.)

On the Texas Side

Before leaving the Southwest, I want to toss in an intriguing Great Serpent mural from the far western corner of Texas, just south of the New Mexico border. (See picture below, a painted reproduction.) It comes from a rock art gallery known as Hueco Tanks. Several historical layers are visible, with the horse-riders added more recently by Apache artists. The older layer shows a white-spotted being flying up toward the Serpent. No clear gender markers, which is typical for much of Texas rock art, but looks female to me.

Double Woman and her Dreamers

Recently I’ve been reading Kelley Hays-Gilpin’s Ambiguous Images: Gender and Rock Art (2004). I sought out this book because I was having trouble (not wanting to make unwarranted assumptions) identifying gender in the rock art of Utah and other regions of western America. It seemed as if the short-kilted figures were male (some had penises, but many others had no clear gender markers) and the long-robed ones were female. But were they? Was there any American Indian testimony on this? (As it turns out, some of these paintings and petroglyphs of the Desert Archaic style are 5000 years old or more, so it is hard to know what the people of that time intended.) Anyway, Hays-Gilpin does a great job of critiquing long-held assumptions that all rock art was made by men, and that it represented males unless breasts were clearly shown. She lays out how a great many of the figures (not just in North America, but in Australia, Siberia and elsewhere) are objectively ungendered. I’m not going to review the whole book, but only touch on a section relating to Lakota rock art: Dreaming of Double Woman on the Northern Plains.

I’ve read about Double Woman before in accounts about Lakota women with medicine powers. She is an important spirit who comes to girls or women in visions or dreams, bringing them the gift of artistic power, and sometimes healing power too. Double Woman Dreamers created many sacred objects, quilled, beaded, painted, tooled leather. It was Double Woman who invented quillwork (a primary art form before trade beads came in). She is also associated with with Deer-Women who symbolize women’s free sexual expression, and female nonconformity to patriarchal sexual double standards.

As Hays-Gilpin explains, such women “could forego marriage and childbearing, and support themselves by doing fine quillwork, leather work, and other crafts. They might live alone or set up a household with another Double Woman dreamer. [Or simply another woman.]” Double Women dreamers also could and did marry men and live out the “good” woman archetype associated with bison. (For more on this subject, including the sexual double standard, see Deer Women and Elk Men: The Lakota Narratives of Ella Deloria. By Julian Rice. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1992.)

The book draws on some very important scholarship by Linea Sundstrom “whose extensive analysis of northern Plains rock art and ethnography shows that some rock art was produced by women who had particular kinds of visions.” Hays-Gilpin summarizes,

Several sources written between the 1830s and 1880s suggest traditions that Double Woman made rock art. Several texts record stories of female spirits that dwell in boulders and make rock art; of sounds like hammering and women’s laughter; and sparks of light in the night, where petroglyphs could be seen the next morning. Oral traditions at several particular sites, including Pipestone, Minnesota, and Ludlow Cave, South Dakota, include references to ‘two women’ who create and periodically renew rock art. [94]

So, Sundstrom writes, “In practical terms, this suggests that Double Woman dreamers made some rock art.” Because little distinction was made between the spirits and those who worked with their powers, “This means that rock art said to be made by female spirits (like Double Woman) may have been made by women influenced by such spirits.” [Sundstrom, 2002a, 106] She proposes that sites with images of “bison and deer tracks, human vulvas, handprints, footprints, and abraded grooves” could reflect the work of such dreamers. Why abraded grooves? This interests me because rock art literature nearly universally attributes them to males sharpening weapons or straightening arrows. But Sundstrom points out that women sharpened their awls and other bone tools in this way. The awl would have been a female tool par excellence, and before metal came in, would have had to be sharpened often. Sundstrom writes,

The grooves used for making and renewing bone awls were symbols of, and prayers for, success in womanly endeavors from craftwork to childbearing… Since Double Woman, the ultimate artist, was said to dwell in the rock, it is likely that some of her essence was thought to be transferred to the tool itself and, thus, to the items the woman made for her family’s use. The prolonged rhythmic grinding motion may have promoted a trance state in which the person making the tool (and the rock art) might be more receptive to a vision. [Sundstrom, 2002a, 109]

Brilliant. And this is borne out by actual sacred sites, as well as a 1930s photo of abraded grooves in the Black Hills that Sundstrom uncovered — which had a note on the back confirming that Lakota women sharpened their tools there. It seems as if they might have done so while simultaneously creating the animal tracks on some of these sites, whcih themselves were sacred places. Hays-Gilpin describes Sundstrom’s conclusion: “the vulva-track-groove art style coincides with known vision quest sites, caves containing many offerings including awls, and it one case, a bas-relief of a buffalo cow with her newborn calf.” (Shown in the photo of Ludlow Cave, above)

All Sundstrom quotes from Hay-Gilpin. (More information about Double Woman here.)

Max Dashu